The summer of 2024 marked the boiling point of a prison overcrowding crisis, caused by ineffective policy decades in the making. Despite releasing prisoners early, the system is still operating at over 98% capacity, as of April 2025, and the government is scrambling for solutions. The 2025 Independent Sentencing Review promises to be a lifeboat off the sinking ship. However, a £7 Billion investment into essentially continuing the Tory government's prison-building project implies that Labour does not see the prison population shrinking any time soon.

The newest prison to be built, HMP Millsike, is run by Mitie Care and Custody, the fourth and newest Private Security provider to enter the Prison Estate in England and Wales, recently signing a £329 million contract to run HMP Millsike from 2025. G4S, Serco, and Sodexo already operate prisons in England and Wales. Considering this new addition, is it time to revisit how we ended up in this crisis and how efficient prison privatisation is at getting us out of it?

Private Prisons and Neoliberal Policy

Privatisation has become a cornerstone of Neoliberal policy. In the UK, the discourse surrounding the privatisation of core state functions has been a perpetual arm wrestle since the 1980s, while progressively becoming a routine development of crucial industries. Neoliberal doctrine argues that inefficiencies in state firms are often a result of these firms pursuing objectives set by politicians. Therefore, it promotes managerial devolution of state functions and that these appendages of the state be left to the market, which will in turn improve efficiency. Since the turn of the century, there has been a noticeable surge in the number of prison contracts awarded to private companies, with all but 1 of the prisons opened after 2001 currently being operated privately. There are currently 14 private prisons in England and Wales and The Ministry of Justice claims that ‘Many privately-run prisons are among the best performing across the estate’; however, there are still many critics of private incarceration.

Proponents of this Neoliberal agenda argue that private construction and management contracts allow for prison spaces to be built quickly and maintained cost-effectively. Furthermore, privatisation champions innovation fostered by free market competition which allows for further efficiency. However, critics would argue that efficiency is simply a distraction and that private organisations function on the market principles of growth and demand. These key tenets are fundamentally opposed to reducing prison populations and therefore inefficient at fixing the overcrowding crisis.

Efficiency or Expansion?

‘Efficiency’ is a key conviction of privatisation and justification for the continued expansion of the private prison industry in the UK, so let's dive into how efficient the UK prison system has been since the introduction of private prisons. The UK’s first private prison, HMP Wolds, opened in 1992, originally planned as a test; it was quickly ushered beyond the trial stages. At this point, private contractors were only permitted to manage prisons and therefore the expansion of the private prison estate was limited, however, after the perceived success of HMP Wolds, the 1994 Criminal Justice and Public order act was passed. This permitted both the operation and now construction of prisons to be contracted or subcontracted to private companies, and by the end of 1994, another 3 privately operated prisons had been opened.

Growing Demand

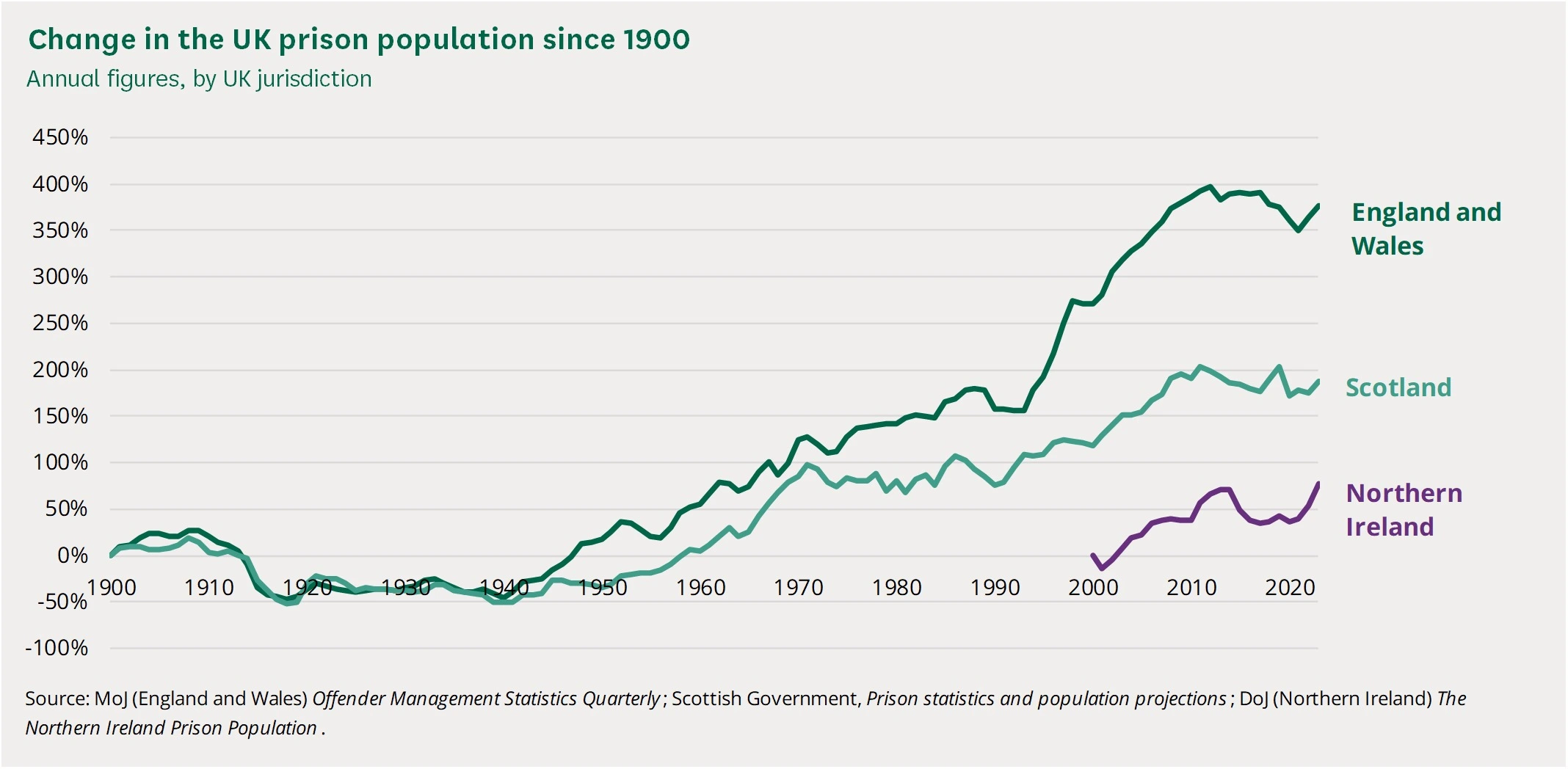

If you look at this expansion in the context of prison populations, it renders a very telling picture. Whilst the early 1990s saw a rare plateau in prison populations, the mid 1990s, concurrent with this expansion of the private prison portfolio, saw a dramatic spike. This increase has not slowed, and has led to the position of overcrowding that we saw climax in the summer of 2024. A situation which led to Secretary of State for Justice Shabana Mahmood dramatically but justifiably warning of ‘‘the collapse of the criminal justice system, and a total breakdown of law and order”.

Sentencing Inflation: Driving Demand to Fill Supply

However, this dramatic rise in prison population is more commonly attributed to the accompanying Criminal Justice Act of 1991. This was a draconian set of sentencing policies increasing both the number of offenders sentenced and the length of those sentences. In combination, this has caused the UK's prison population to more than double since 1991 and the average custodial sentences to rise from 13 months to 21 months in the last 20 years.

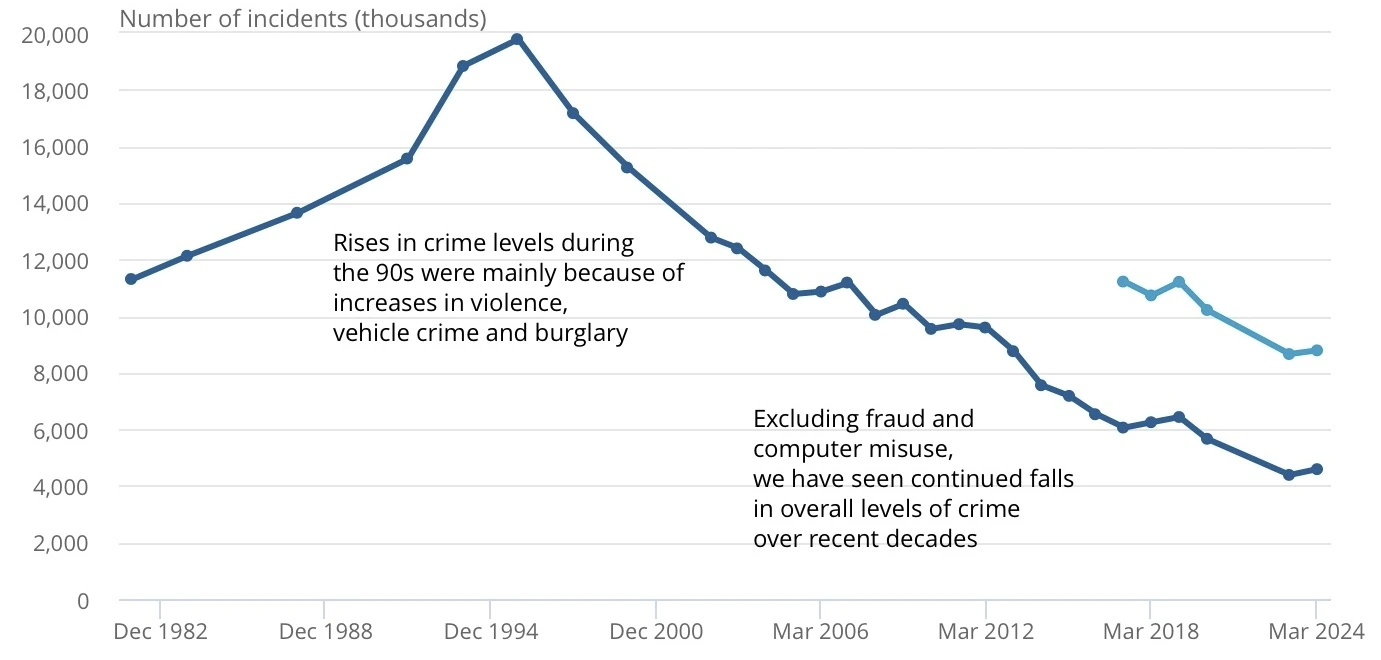

This push for harsh penal policy and overt sentencing inflation was justified by politicians and the media as a way to make communities safer and was sold as “tough on crime”. Despite this national moral panic, the Office for National Statistics has actually shown an opposite trend with crime rates rapidly decreasing since the early to mid 1990s. With a timely increase in the prison population accompanying the introduction of private prisons, all whilst crime rates are steadily falling, it is difficult to see the efficiency which neoliberal policy predicts and government proponents promise. Especially when you consider it costs over £50,000 a year to keep one person incarcerated, the most cost efficient plan would be to minimise the incarcerated population.

The trends in prison population compared to crime rates force the binary relationship between crime and punishment into disregard. Sentencing inflation, driven by policies such as the Criminal Justice Act of 1991, has had a profound impact on prison overcrowding and thus the need to continually expand the prison estate. However, this sentencing inflation has not been fed through crime but through an inflated perception of crime, and the only way off this train heading for inevitable de-railing is to reverse the policies which have led us here.

2025 Sentencing Review : Substantive or Superficial?

Luckily, the Ministry of Justice has promised that the 2025 independent sentencing review will bring about “landmark” reforms to these very policies. Signs were initially promising, with a number of positive recommendations, tackling recall and short sentences as well as promoting more community punishments. Chair of the review, David Guake, even highlighted longer sentencing as the root of the crisis; however, the published report then offers no tangible recommendations to address this issue. When questioned on this omission, Gauke cited a lack of time and resources, signposting his other recommendations as “the easier course to pursue”. Considering last summer, the government warned of "a total breakdown of law and order”, this does not reflect a process claiming to “ensure prisons never run out of space again”, as the MOJ claims.

Even more worryingly, the number of prison spaces quoted as being created by the recommendations in the review is 9800, only 300 more spaces than the MOJ has projected the growing demand will be. David Gauke's plan to reduce the prison population would only just cover the amount needed and therefore a small miscalculation could push the prison estate straight back to the brink of collapse. In his defence, Guake claims that gains from reduced recall populations and deportation of foreign nationals, both central aspects of the review, are not included in the calculation of how many spaces can be created. However, this does little in terms of reassurance and instead suggests a deliberate underreporting of the figures. It carefully manages a reformist headline whilst avoiding undermining the recent £7 billion investment into Labour's prison building programme, promised in the 2025 spending review. Which, in line with current trends, will be drip fed into the private sector.

In fact, the review endorses additional private sector investment, expanding the £200 million tagging project, contracted to Serco, despite Serco’s overt mismanagement that left prison leavers unmonitored for months. Alongside this, Shabana Mahmood has also recommended an increase in community sentences being served in unpaid work for private sector companies. Early signs indicate the review is, yet again, a temporary bandage, obfuscating the critical issues plaguing the prison system. If anything, this review only further cements the government's agenda to keep building prisons and heavily relying on the private sector to do so.

At Odds: Privatisation and Prison Reduction

To create a long-term solution to the overcrowding issue, the long-standing harsh penal policies promoting more frequent and longer prison sentences must be overturned. Championing rehabilitation as well as supporting prison leavers to stay out of prison is crucial. This in turn we gradually remove the current need to expand the prison estate. Instead, a plan to scale down the system can be enacted, allowing for investments, like the £7 billion earmarked for the government's prison building scheme, to be redirected into projects aimed at reducing reoffending and preventing the causes of crime.

However, this is likely to collapse the private prison market. Without demand or a tangible growth model, companies will no longer see it as a profitable investment, and the market will cease to exist.This leads me to believe that there is no end in sight. In a structure now so deeply intertwined with the free market, this crisis has become self perpetuating and creates demand for the very system that has caused it.

Dylan Clarke-stock

Dylan Clarke-stock